Introduction

Transfection is a pivotal technique in molecular biology and genetic engineering, allowing for the introduction of nucleic acids, such as DNA, RNA, and mRNA, or other molecules, like proteins and CRISPR components, into cells. This process enables researchers to study gene function, protein expression, and cellular behavior in both normal and manipulated states.

There are three common methods of delivering these molecules: chemical, physical, and viral. Chemical transfection methods include the use of calcium phosphate, liposomes, and polymers like polyethyleneimine (PEI), which form complexes with DNA to facilitate its entry into cells. Physical transfection methods, such as electroporation and biolistic particle delivery, involve the physical relocation of nucleic acids into cells. Viral transfection, also known as transduction, uses viruses as vectors to carry genes into cells. Each method has its own advantages and limitations, and the choice of method often depends on the specific requirements of the experiment and the cell type being used. Here we will focus on chemical and physical transfection methods.

The History of Transfection

The concept of transfection dates back to the mid-20th century. Initially, scientists discovered that viruses could introduce genetic material into host cells, leading to studies on nonviral methods of gene transfer. In the 1970s, the first successful DNA transfections were performed using calcium phosphate co-precipitation, laying the groundwork for further advancements. This method, described by Graham and van der Eb in 1973, was followed by various other techniques that increased the efficiency and specificity of gene delivery (Graham and van der Eb 1973).

Transient vs. Stable Transfection

Transfection can be categorized into two types: transient and stable. In transient transfection, the introduced nucleic acids and other molecules do not integrate into the host genome, resulting in temporary expression of the transfected gene. This type is useful for short-term studies of gene function or protein expression. However, the expression typically diminishes over time as the nucleic acids and other molecules are degraded or diluted during cell division (Recillas-Targa et al. 2006)

Stable transfection involves the integration of the transfected gene into the host genome, allowing for permanent gene expression in the progeny of the transfected cells. This is achieved by selection for cells expressing resistance markers to antibiotics or drugs over several weeks (Recillas-Targa et al. 2006). Stable transfection is essential for long-term studies and the production of recombinant proteins, but it requires more time and effort to establish.

-

Already know what you're looking for?

Featured Content

Methods of Transfection

There are several methods used to transfect cells, each with its own advantages and limitations.

Chemical Methods

Chemical transfection methods include the use of calcium phosphate, liposomes, and polymers such as PEI. These chemicals form complexes with DNA, facilitating its entry into cells. While these methods generally cause less cellular stress than physical methods, they can be less efficient and may require optimization for different cell types (Boussif et al. 1995).

Calcium Phosphate Transfection

Calcium phosphate transfection involves mixing DNA with calcium chloride and then adding this mixture to a buffered saline/phosphate solution. This results in the formation of a fine precipitate that can adhere to cell membranes and be taken up by endocytosis. This method is cost-effective and simple, but its efficiency can vary widely depending on the cell type and the exact conditions used. Additionally, the precipitate can sometimes be too large, leading to cell death or inconsistent transfection results.

Lipid-Mediated Transfection

Liposome-mediated transfection, also known as lipofection, uses lipid vesicles to encapsulate the nucleic acids. These liposomes fuse with the cell membrane, releasing their contents into the cell. Lipofection is widely used because it is relatively gentle on cells and can be highly efficient. However, the lipid formulations often need to be optimized for different cell types, and the transfection efficiency can be affected by factors such as the size of the DNA and the presence of serum in the culture medium.

Polyethyleneimine (PEI) Transfection

PEI is a cationic polymer that can condense DNA into positively charged particles, which can then interact with the negatively charged cell membrane and be taken up by endocytosis. PEI is versatile and effective for both transient and stable transfections, and it works well with a variety of cell types. However, high concentrations of PEI can be toxic to cells, and the process often requires careful optimization to balance efficiency and cell viability. Each of these chemical methods offers advantages and challenges, and the choice of method often depends on the specific requirements of the experiment and the cell type being used.

Transfection can be accomplished using chemical, biological, or physical methods. Common methods include electroporation, the use of a virus vector, lipofection, and biolistics. Many types of genetic material, including plasmid DNA, siRNA, proteins, dyes, and antibodies, may be transfected using any of these methods. However, a single method cannot be applied to all types of cells; transfection efficiencies and cytotoxicity may vary dramatically and depend on the method, cell type being utilized, and types of experiments being performed. Therefore, to obtain high efficiencies, all relevant factors should be considered for planning and selecting the appropriate transfection method.

TransFectin Lipid Reagent

Physical Methods

Physical transfection methods, including electroporation and biolistic particle delivery, are a more recent development than chemical methods. They involve the physical relocation of extrachromosomal nucleic acids (plasmid DNA, cDNA, mRNA, miRNA, siRNA) and other molecules, such as ribonucleoproteins (RNPs), into cells and do not require a viral vector. Whilst these methods rely on physical forces to introduce nucleic acids and other molecules into the cells, they can also cause damage to cells, which can be addressed with optimization.

Electroporation

Electroporation involves applying an electric field to create transient pores in the cell membrane, allowing nucleic acids and other molecules to enter (Neumann et al. 1982). This method is highly efficient for a wide range of cell types and molecules and can be used for both transient and stable transfections. In some cases, the process can be harsher on certain cells, leading to cell death in sensitive cell lines. Adjusting parameter settings allows for optimizing conditions to obtain the highest viability and transfection efficiency for inherently difficult cells, like primary mammalian cells.

MicroPulser Electroporator

The MicroPulser Electroporator is a versatile, easy-to-operate instrument, providing reproducible, safe transformation of bacteria, fungi, and other microorganisms.

Gene Pulser Xcell Total System

The Gene Pulser Xcell Total System includes both the PC module and the CE module and provides full capability to electroporate both eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells using either exponential or square wave pulses.

Gene Pulser Xcell Eukaryotic System

The Gene Pulser Xcell Eukaryotic System enables electroporation of mammalian cells and plant protoplasts.

Gene Pulser Xcell Microbial System

The Gene Pulser Xcell Microbial System enables electroporation of bacteria and fungi, as well as other applications where high voltage pulses are applied to samples of small volume and high resistance.

Biolistic Particle Delivery

The biolistic particle delivery, or gene gun, method first described by Klein et al. (Klein et al. 1987) involves coating DNA or RNA onto micron-sized gold or tungsten particles and physically shooting them into cells using high-velocity gas pulses. This technique is particularly useful for plant cells and tissues that are difficult to transfect using other methods, including living intact plants and animals, allowing researchers to carry out experiments on whole organisms instead of just tissue cultures. Although effective, it requires specialized equipment and can cause physical damage to cells.

Helios® Gene Gun System

Microinjection

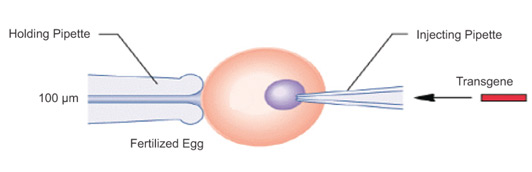

Microinjection is a precise and direct method of transfection that involves using a fine glass needle or micropipette to introduce genetic material into individual cells. This method is particularly useful for applications such as single-cell manipulation, the generation of transgenic animals, and various research areas, including genetic engineering and genome editing. The process is performed under a powerful microscope, where the micropipette is carefully inserted through the cell membrane, either into the cytoplasm or the nucleus, depending on the target location for the genetic material. Although microinjection is highly effective, it is time-consuming and requires specialized equipment and significant skill to perform.

Transgene Microinjection

Laserfection

Laserfection, also known as optoinjection, is an advanced transfection method that uses laser light to introduce nucleic acids into cells. It is especially beneficial for research areas such as gene therapy, genetic engineering, and cellular biology. This technique involves focusing a laser beam to create a transient pore in the cell membrane. The process is highly precise and can target individual cells, making it particularly useful for single-cell analysis and applications requiring high specificity. While this method offers significant advantages in terms of precision and control, it requires specialized equipment and expertise to perform.

Methods Summary

Table 1: Non-viral delivery methods

| Type | Method | Recommended Cells | Products |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical | Lipid-mediated | Immortal cells, adherent (attached), or suspension cells |

TransFectin lipid reagent SiLentFect lipid reagent |

| Physical | Electroporation | Eukaryotic cells (primary, stem cells), prokaryotic cells (bacteria, yeast), plant protoplasts |

Gene Pulser Xcell™ electroporation system MicroPulser™ electroporator |

| Biolistic particle delivery | Plant (intact, cell culture and explants, pollen), primary cells, tissue, yeast, bacteria, microbes, insects, and in vivo applications |

Helios™ gene gun PDS-1000/He™ biolistic particle delivery system |

Featured Content

Factors Influencing Transfection Efficiency

Several factors can influence transfection efficiency and viability, including:

- Cell type: different cells have variable permeability and susceptibility to transfection

- Delivery molecule(s): different molecules, combined with a particular cell type, will impact the efficiency and viability. For example, DNA plasmids are much more challenging to deliver, in a similar efficiency and viability, than mRNA

- Method of transfection: each method has its own efficiency rates and often requires optimization

- Quality and quantity of molecules: purity and concentration of DNA or RNA can significantly impact transfection success

- Cell health: cells should be in optimal condition, typically at a logarithmic growth phase, for best results

- Transfection reagent: the choice and concentration of chemical transfection reagents need careful selection and optimization

Optimizing these factors is crucial for achieving high transfection efficiency, viability, and reproducible results.

Measuring Transfection Efficiency & Downstream Analysis

Once gene delivery has been completed, it is important to verify how effective the transfection procedure has been. Various techniques are available for post-transfection analysis, including cell counting, flow cytometry, western blotting, imaging, real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR), and droplet digital PCR (ddPCR). The most appropriate technique will depend on the specific downstream application, the gene that has been transfected, and the cell type used.

Featured Content

References

- Boussif O et al. (1995). A versatile vector for gene and oligonucleotide transfer into cells in culture and in vivo: polyethyleneimine. Proc Natl Acad Sci, 92, 7297–7301.

- Graham FL and van der Eb AJ (1973). A new technique for the assay of infectivity of human adenovirus 5 DNA. Virology, 52, 456–467.

- Klein TM et al. (1987). High-velocity microprojectiles for delivering nucleic acids into living cells. Nature, 327, 70–73.

- Neumann E et al. (1982). Gene transfer into mouse lyoma cells by electroporation in high electric fields. EMBO J 1, 841–845.

- Recillas-Targa F (2006). Multiple strategies for gene transfer, expression, knockdown, and chromatin influence in mammalian cell lines and transgenic animals. Mol Biotechnol 34, 337–354

Featured Content

Related Content

Videos

- The Preparation of Primary Hematopoietic Cell Cultures From Murine Bone Marrow for Electroporation

This video protocol describes the preparation of primary hematopoietic cell cultures from murine bone marrow for electroporation. - Using an Automated Cell Counter to Simplify Gene Expression Studies: siRNA Knockdown of IL-4 Dependent Gene Expression in Namalwa Cells

Outlines a simple workflow for introducing siRNA into challenging cell lines and monitoring gene expression via real-time PCR. Using an automated cell counter, multi-well electroporation plate, and automated electrophoresis station ensures quick, reliable results without costly robotic handling. - Using the Gene Pulser MXcell Electroporation System to Transfect Primary Cells with High Efficiency

Explains the use of the Gene Pulser MXcell electroporation system for determining optimal electroporation conditions for mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) or other primary cells. The video also covers considerations for troubleshooting. - Preparation of Gene Gun Bullets and Biolistic Transfection of Neurons in Slice Culture

A method for preparing DNA-coated gold bullets is described, along with their application for biolistically transfecting neurons in cultured hippocampal slices. - Gene Pulser Xcell™ Electroporation System: Components, Application, and Troubleshooting

This tutorial highlights the main components and features of the Gene Pulser Xcell system. It provides information about system installation and the setup of electroporation experiments, including important troubleshooting tips and answers to frequently asked questions. Ordering information for system components and accessories is also provided.

Documents

Selection Guides

Articles

- Top 8 Advantages of Electroporation in Cell and Gene Therapy

This article outlines the top advantages of using electroporation in cell and gene therapy and why it might be a good approach for your own research group.

- GMP-Compliant Production of CAR-T Cells Using mRNA Transfection

This article explores a study that described a method using mRNA transfection to generate CAR-T cells targeting melanomas at the clinical scale, under full GMP compliance.